Many autistic adults describe a confusing and exhausting social position: being treated as both incompetent and competent, sometimes by the same people, sometimes within the same relationship.

This pattern is not random. It follows a recognizable structure that is persistent.

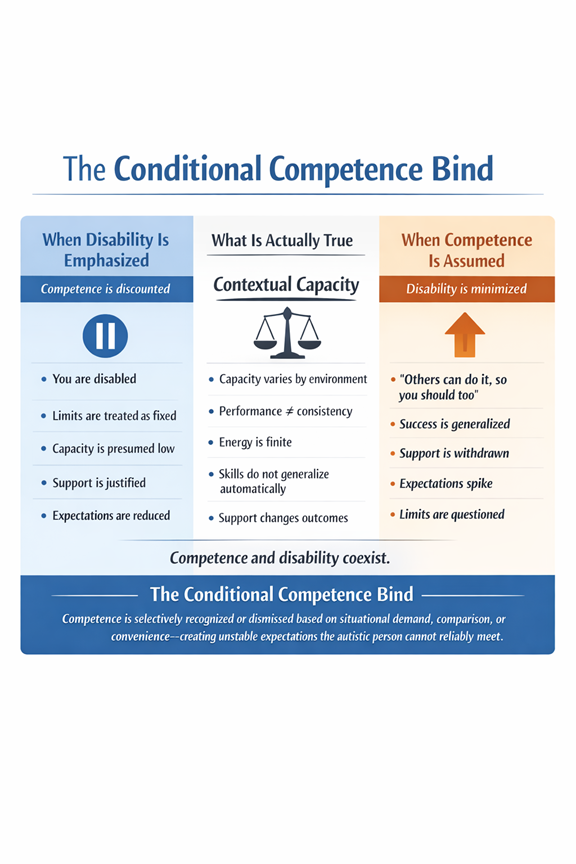

I refer to this dynamic as the Conditional Competence Bind.

The Conditional Competence Bind occurs when an autistic person’s competence is selectively recognized or dismissed depending on situational expectations, comparisons to others, or perceived demands. The Conditional Competence Bind results in unstable, contradictory expectations that the individual cannot reliably meet or resolve.

In the Conditional Competence Bind, disability is invoked to explain limitations while competence is simultaneously presumed when performance is desired. This creates a fluctuating standard in which autistic adults are alternately treated as incapable and fully capable, without acknowledgment of contextual capacity, energy limits, or consistency constraints.

The bind often emerges in ordinary family interactions.

At one point, an autistic person is told, explicitly or implicitly, “You are disabled.” The statement may be framed as protective or explanatory. It becomes part of how others understand the person’s limits, needs, and identity.

Later, that same person may hear enthusiastic stories about another autistic individual - someone who struggled but is now succeeding in a highly visible way. The emphasis is often on surprise or triumph.

The message shifts without warning.

Disability is treated as a fixed explanation in one moment and as a temporary obstacle in the next. Competence is acknowledged when it is impressive or comparative, but assumed when expectations need to be met.

This is the Conditional Competence Bind in action.

Most people caught in this dynamic are not acting with malice.

When disability is emphasized, the intention is often:

When competence is highlighted, especially through comparison, the intention is often:

Each message, taken alone, sounds supportive. Each intention may even make sense in isolation. The problem is not intent. The problem is inconsistency. Inconsistency creates instability.

From the autistic person’s perspective, the Conditional Competence Bind creates an unstable social environment.

Support is offered, but unpredictably. Limitations are acknowledged, but selectively. Expectations expand or contract without explanation.

Disability explains why something cannot be done, until someone else does it. Competence is celebrated, until it is demanded.

Over time, this erodes clarity. Autistic adults are left unsure which version of themselves others are responding to: the one who requires accommodation, or the one who should already be capable.

The Conditional Competence Bind is sustained by incompatible models of disability operating at the same time.

One model treats disability as fixed and defining. Another treats it as something that can be overcome through effort, maturity, or comparison.

Autistic functioning does not conform to either model.

Capacity is contextual. Performance is variable. Consistency is not guaranteed.

Recognizing competence in one setting does not erase disability in another. Expecting generalization where none exists is a category error, not optimism.

Living inside the Conditional Competence Bind has real consequences.

It complicates planning and self-advocacy. It fosters chronic self-doubt. It discourages disclosure of limitations for fear they will later be invalidated.

Most importantly, it places the burden of reconciliation on the autistic person by asking them to resolve contradictions they did not create.

The solution is not to lower expectations or raise them indiscriminately.

It is to stabilize them.

Competence and disability are not opposites. They coexist.

Autistic adults are not selectively capable. They are contextually capable.

Releasing the Conditional Competence Bind requires holding both realities at the same time without using one to negate the other.

"*" indicates required fields